In the vast, frost-kissed landscapes of Northeast China, a silent sentinel of ecological health has emerged. Jiao Wang, a researcher from the College of Geographical Science at Harbin Normal University and the Heilongjiang Province Key Laboratory of Geographical Environment Monitoring and Spatial Information Service in Cold Regions, has developed a groundbreaking tool to assess the ecological quality of wetlands in permafrost regions. Published in the journal *Ecological Indicators* (which translates to *生态指标* in Chinese), this research could significantly impact the energy sector’s approach to wetland management and conservation.

Wetlands in permafrost regions are critical ecosystems, acting as nature’s sponges to regulate water flow, support biodiversity, and store vast amounts of carbon. However, these delicate habitats are under threat from climate change and human activities. Traditional assessment methods often fall short, lacking the ability to rapidly monitor large areas and account for the unique influence of permafrost.

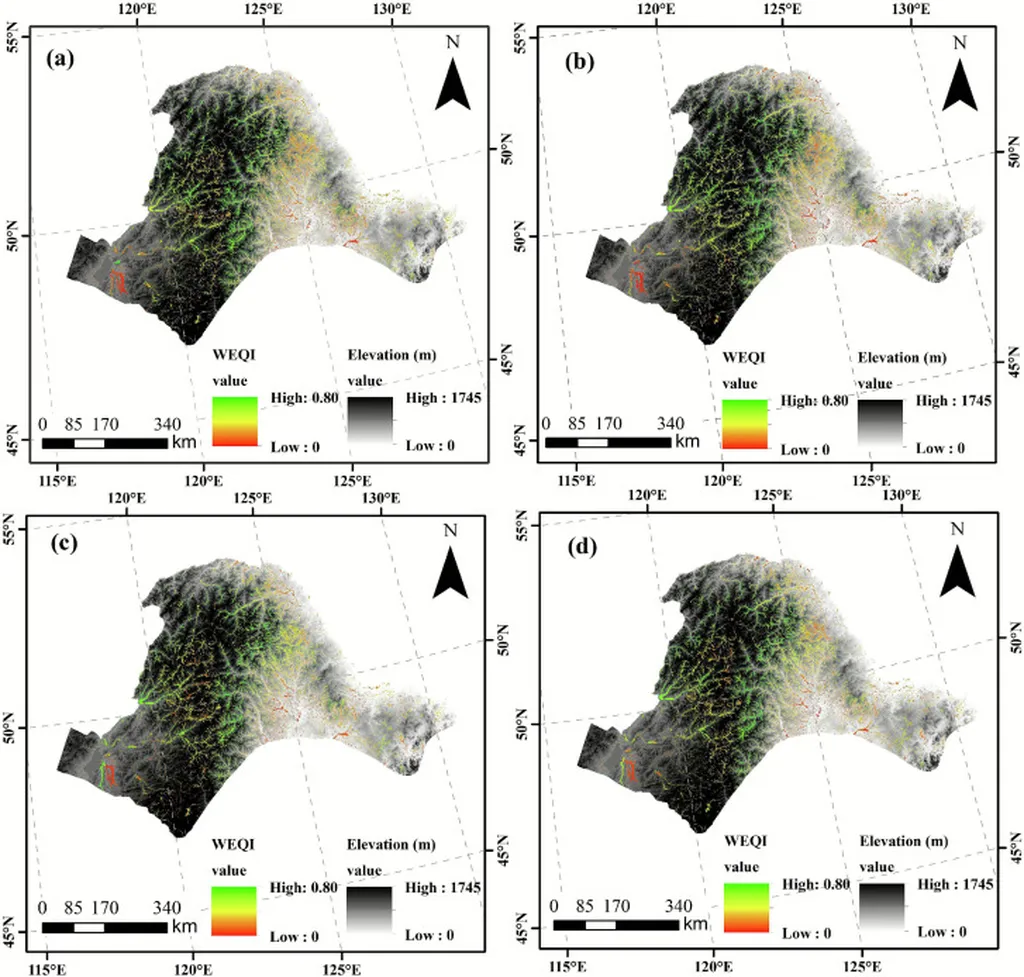

Enter the Wetland Ecological Quality Index (WEQI), a novel framework that integrates multiple variables, including remote sensing-derived indicators like wetness, vegetation abundance, and soil moisture, along with topographical data. “WEQI provides a comprehensive and dynamic assessment of wetland ecological quality,” Wang explains. “It’s a tool that can help us understand the spatiotemporal dynamics of these ecosystems over time.”

The study, which analyzed data from 2001 to 2020, revealed some surprising trends. Despite the increasing fragmentation and irregular shapes of wetland patches, the overall ecological quality of these wetlands has shown a slight improvement over the past two decades. This paradoxical finding was corroborated by assessments using the InVEST model, a tool often used to quantify the benefits that nature provides to people.

The research also identified the primary drivers of these changes across different permafrost zones. “In different permafrost regions, the combined influence of ground temperature and other factors is more pronounced,” Wang notes. This insight is crucial for the energy sector, as it highlights the need for tailored conservation and management strategies that consider the unique characteristics of each permafrost zone.

The implications of this research are far-reaching. For the energy sector, understanding and preserving wetland ecological quality is not just an environmental imperative but also a commercial one. Wetlands play a crucial role in regulating water flow, which can impact hydropower generation. They also store vast amounts of carbon, making their preservation a key strategy in mitigating climate change.

Moreover, the WEQI tool offers a practical solution for the rapid, continuous monitoring of wetland ecosystems over large areas. This capability is invaluable for energy companies operating in these regions, as it enables them to assess and mitigate their environmental impact more effectively.

As we look to the future, the WEQI framework could shape the development of new conservation strategies and policies. It could also pave the way for more integrated approaches to wetland management, where ecological health is considered alongside economic and social factors.

In the words of Jiao Wang, “WEQI is more than just a tool; it’s a step towards a more sustainable future for our wetlands and the communities that depend on them.” For the energy sector, this research offers a compelling case for investing in wetland conservation and management, not just as a corporate social responsibility initiative, but as a strategic business decision.