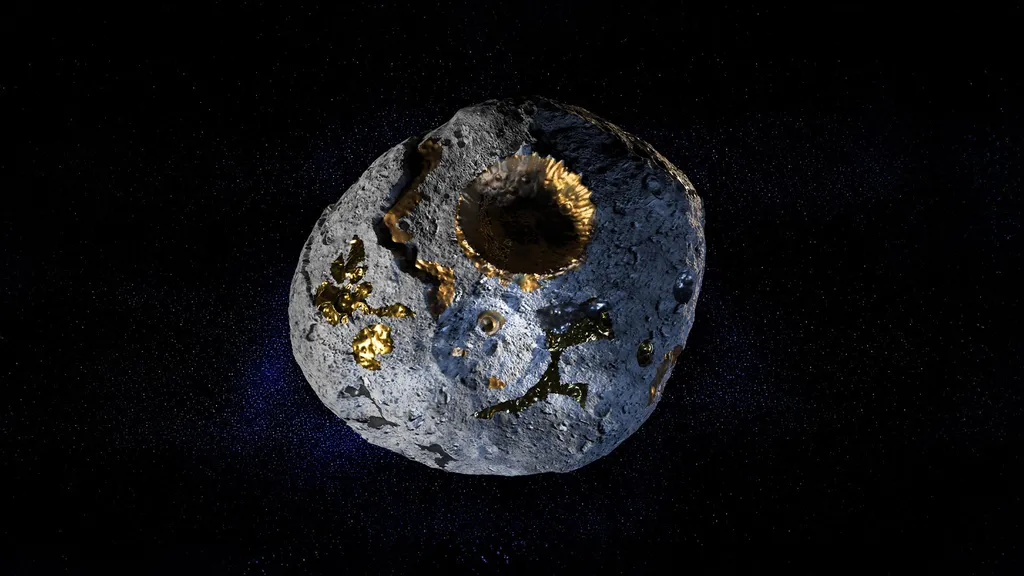

Scientists have long been intrigued by the potential of small asteroids as sources of valuable materials and scientific insights. These rocky bodies, remnants from the solar system’s formation, may harbor precious metals, ancient materials, and chemical clues about their parent bodies. A recent study led by the Institute of Space Sciences (ICE-CSIC) has strengthened the case for carbon-rich C-type asteroids as important material reservoirs, potentially shaping the future of space resource development.

The study, published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, focused on carbonaceous chondrites, rare meteorites that originate from these asteroids. These meteorites account for only about 5% of all meteorite falls and are often found in desert environments like the Sahara or Antarctica, where preservation conditions are favorable. “The scientific interest in each of these meteorites is that they sample small, undifferentiated asteroids, and provide valuable information on the chemical composition and evolutionary history of the bodies from which they originate,” says Josep M. Trigo-Rodríguez, the study’s lead author and an astrophysicist at ICE-CSIC, affiliated to the Institute of Space Studies of Catalonia (IEEC).

To understand the potential of these asteroids as resources, the ICE-CSIC team selected and characterized samples before sending them for detailed chemical analysis using mass spectrometry. This work allowed the researchers to determine the precise chemical makeup of the six most common types of carbonaceous chondrites and assess the practicality of extracting materials from their parent asteroids.

The findings suggest that while asteroid resources may be valuable, their extraction is not yet practical on a large scale. “Studying and selecting these types of meteorites in our clean room using other analytical techniques is fascinating, particularly because of the diversity of minerals and chemical elements they contain. However, most asteroids have relatively small abundances of precious elements, and therefore the objective of our study has been to understand to what extent their extraction would be viable,” says Pau Grèbol Tomás, a predoctoral researcher at ICE-CSIC.

The team also highlights the challenges of extracting resources from asteroids covered in regolith, a loose surface material. “Although most small asteroids have surfaces covered in fragmented material called regolith—and it would facilitate the return of small amounts of samples—developing large-scale collection systems to achieve clear benefits is a very different matter,” says Jordi Ibáñez-Insa, a co-author of the study and researcher at Geosciences Barcelona (GEO3BCN-CSIC).

The main asteroid belt contains a vast range of objects, and understanding their resources requires careful classification. Trigo-Rodríguez notes that asteroid composition varies widely due to their complex histories. “They are small and quite heterogeneous objects, heavily influenced by their evolutionary history, particularly collisions and close approaches to the Sun. If we are looking for water, there are certain asteroids from which hydrated carbonaceous chondrites originate, which, conversely, will have fewer metals in their native state.”

The study concludes that mining undifferentiated asteroids remains impractical for now. However, the team identifies a different class of relatively pristine asteroids that display olivine and spinel signatures as more promising mining targets. To confidently identify such candidates, the researchers emphasize the importance of detailed chemical studies of carbonaceous chondrites combined with new sample return missions.

The findings could have significant implications for the future of space exploration and resource development. As in situ resource use becomes increasingly important for long-duration missions to the Moon and Mars, using materials found in space could significantly reduce the need for supplies launched from Earth. “Alongside the progress represented by sample return missions, companies capable of taking decisive steps in the technological development necessary to extract and collect these materials under low-gravity conditions are truly needed,” Trigo-Rodríguez adds.

The team expects progress in the near future, especially as water becomes a primary target for space missions. Extracting resources in low gravity environments will require entirely new approaches. “It sounds like science fiction, but it also seemed like science fiction when the first sample return missions were being planned thirty years ago,” says Pau Grèbol Tomàs.

Globally, several concepts are already being discussed, including capturing small asteroids that pass close to Earth and placing them into circumlunar orbit for study and resource use. Trigo-Rodríguez highlights that water-rich carbonaceous asteroids may be especially attractive targets. “For certain water-rich carbonaceous asteroids, extracting water for reuse seems more viable, either as fuel or as a primary resource for exploring other worlds. This could also provide science with greater knowledge about certain bodies that could one day threaten our very existence. In the long term, we could even mine and shrink potentially hazardous asteroids so that they cease to be dangerous,” he explains.

As the mining industry looks to the stars, the insights from this study could shape the development of